The Nth Wave is a solo exhibition by Theodore Koterwas. Learn more about Koterwas’s use of Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) on images of Scottish seasides and interact with the exhibition.

Exhibition details

Wednesday, 5th to Sunday, 16th of May 2021

open to view at Inspace City Screen at street level on Potterrow from 8pm to 1am

1 Crichton Street, Edinburgh, EH8 9AB

Search for #TheNthWave on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook to see more.

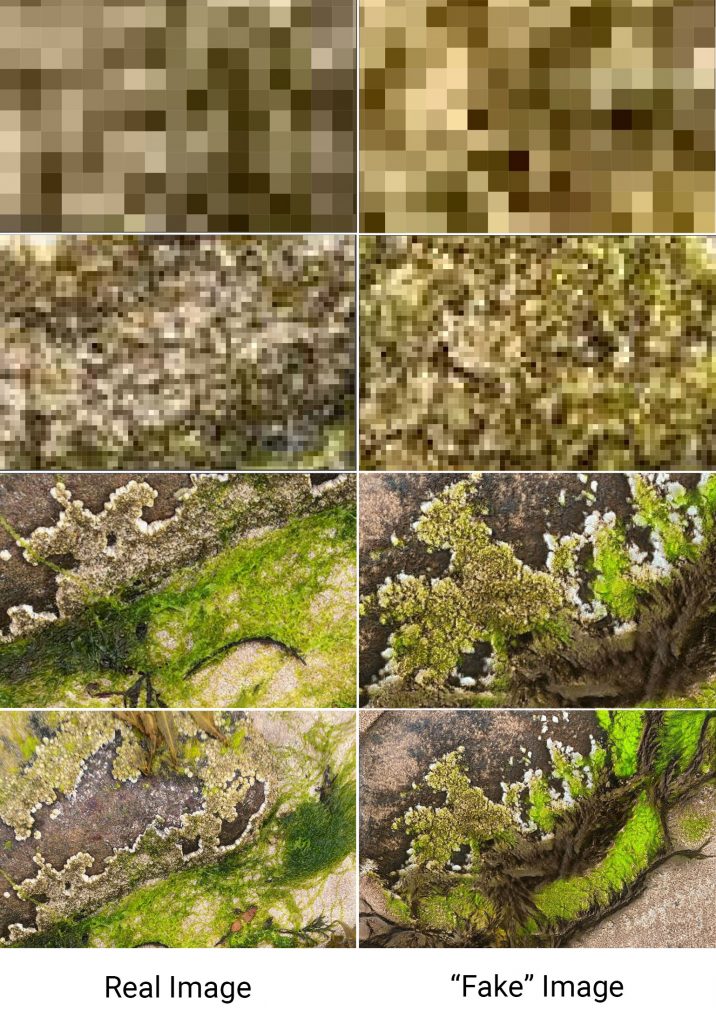

Half of the images you will see are fake. The seaweed, rocks, barnacles, shells and sand never existed in the photos taken, the real images. They were generated pixel by pixel, by an AI, for the fake images.

- Can you tell which images are real?

- What makes the fake images different from the real?

- If you hadn’t been told some were fake, do you think you would have noticed?

- How closely do you need to look to see the differences?

- Would you normally look at things around you this closely?

THE PROJECT

Tide pools exist in two environments, land and water, much how we exist in the real and virtual worlds. It’s theorised they are where life emerged from the sea to evolve into the complex variety of species we see today.

The Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) that created the images in The Nth Wave followed an “evolutionary” process of its own. Exposed to a large number of photographs taken at the seaside, one part of the GAN created new images while another part attempted to discriminate the real from the fake: a sort of silicon survival of the fittest. It also used a lot of energy to compute them.

Similarly, the power consumed to generate “deep fakes”, bots, virtual assistants, and VR experiences creating our collective techno-illusion threatens to not only compete with the natural world for our attention and our concept of “truth” but to literally destroy it.

Our technologies are slick and precise, and so it is usually those qualities we associate with the artificial and the organic qualities of grittiness and unruly-ness we associate with the “real”. Technology is just as capable of creating these qualities as well, and as we watch these convincing fake images wash over the real ones we can be lulled into forgetting which world is which.

THE PROCESS

The Nth Wave exhibition uses WebSockets to keep track of the number of connected devices and then sends each one a timing signal for when they should trigger the “wave” of a fake image washing over a real image. I generated the fake ones using StyleGan2 from 900 real images of tidepools I took at Seacliff Beach, Applecross, Big Sand and the Isle of Harris.

StyleGan2 works by having two neural networks. One attempts to generate images similar to the real ones and the other network feeds back whether it “thinks” the images are real. This optimises the first network toward producing increasingly realistic images. The training will reach a maximum optimisation and then start getting worse. It essentially gets in a rut and begins producing images that look more like textural patterns than images of real things. At this point I had to go back and find where it was optimal. For these images that point was after about 25 hours of training. I could then use that iteration of the network to generate new images, as many as I liked: a potentially infinite number of fake tidepools.

It’s here that I really needed to consider what the piece was about. I could generate the images in real time, continuously 24 hours a day. This would require a server running a fairly expensive process indefinitely, eating up electricity and contributing to climate change. I figured it’s enough just to know this is possible. What’s really interesting is that the images are credible replacements for the real ones, that unless you look closely it’s difficult to see the difference, and that for most of the things we see around us we don’t look that closely. So I decided to generate a finite number of images. The next question was how many? An arbitrary number or something more symbolic? I settled on 706, which I calculated to be the number of tides in a year.

Software for generating fake images and video is now accessible to anyone with a laptop, internet connection and a bunch of pictures. It requires minimal technical knowhow. The implication of this is at the heart of this piece: that convincing synthetic realities are easy for us to create, and at a time when the old markers of truth and evidence are being devalued in favour of collective and tribal “certainty” of the way the world is. Our alternative facts are now trivial to produce, and they wash over us repeatedly, each time reinforcing their impact on what we believe.

THE DATA

Images are both comprised of data and convey data. Each pixel of an RGB colour image is comprised of 24 bits of data and it conveys a colour. Each group of pixels is made up of several more bits and conveys shapes. Our perceptual system turns those colours and shapes into information without regard for the bits behind them. A neural network on the other hand sees only the bits. In computer vision applications, some combinations of bits will have been given the label “cat” and others “banana”. The neural network is fed those combinations of bits and adapts itself so that it is increasingly accurate in assigning the right labels to them. In the case of a GAN like StyleGan it isn’t given labels, just images. One part of it generates new data, new combinations of bits, and then another part, the discriminator, tries to distinguish those combinations from the combinations of bits comprising the real images. The first network adapts itself to produce combinations that the discriminator can’t distinguish from the real ones. It doesn’t care what data the images it produces convey. It hasn’t a clue. It only concerns itself with the data they are comprised of and whether that can be distinguished from the data it was given.

We, of course, do care about the data conveyed by an image. It makes a difference to us if it produces an image of a cat or a banana. We don’t want to eat the cat! Even more so, it matters if the image is of something that exists—that the data conveyed by the image has a direct connection to the thing from which the data comprising the image was generated (by light bouncing off it onto sensors in the camera). Even doctored photographs have some element of this truth to them: at least some of the data conveyed by the image has this connection to a real thing even if it has been altered after the fact. With GAN-generated images this last tenuous connection between the data comprising an image and the data it conveys is severed. Not one bit of data in these images ever bounced off a real object. Yet they convey data to us convincingly.

And of course for this piece, the data conveyed by the images is important. Images of life in the liminal zone between land and sea convey information about the health of our planet, biodiversity, evolution and the origins of organic life. They also convey poetic connotations and memories. So much of what it means to be a human on earth is encapsulated in the seashore. And yet, are we looking closely enough?

THE ARTIST

Theodore Koterwas received his MFA from the San Francisco Art Institute. Early installations included projecting the reflection on the head of a single pin onto the heads of 45,000 others, attempting to shatter glass with amplified water drops, and filling an intimate interior space with the live sound of approaching footsteps.

At the Exploratorium in San Francisco he collaborated with scientists to create digital installations exploring the science of perception. Work included a projection of a street scene that changed completely without you noticing and a video of a theft in which the culprit appears to change just by choosing camera angles.

Moving to Edinburgh in 2006 he performed as experimental music act The Foundling Wheel, and created collaborative gig night Versus. Since then he developed work for the University of Oxford including an app turning phones into historic musical instruments. Returning to Edinburgh in 2017 he produced Eyes I Dare not Meet In Dreams, a digital installation in which he turned 8 people into 56 others without anyone noticing.

Commissioned to produce an installation for the 2020 Edinburgh Science Festival, he participated in its digital edition with the generative composition Skin Wood Iron. His practice is concerned with uncovering quirks and incongruities in everyday perception and making them resonate.

He seeks to create something big out of things that seem small, to make magic from the mundane, and provoke engagement out of apathy.

CREDITS

Concept, Coding, and Photography:

Theodore Koterwas

StyleGan2:

Tero Karras, Samuli Laine, Miika Aittala, Janne Hellsten, Jaakko Lehtinen, Timo Aila